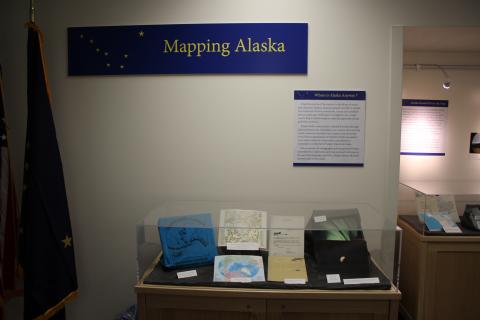

Susannah Dowds talks about her latest exhibit in the Senator Ted Stevens Gallery, November 2013

Monday, November 18, 2013, the Ted Stevens Papers Project marked the 90th anniversary of Ted Stevens’ birth with a day of events and activities. Project Archivist Mary Anne Hamblen and oral historian Karen Brewster of Project Jukebox began the day with an interview with Marie Matsuno Nash, an Alaskan who served as a member of the Senator’s staff for decades. Later, guests gathered for an evening of cake, reminiscing and the opening of Northern Studies graduate student Susannah Dowds’ exhibit, Mapping Alaska. Below is a selection from Susannah’s gallery talk.

The story of this exhibit starts with a pair of shoes. Last April, toward the end of the semester I came home after an exhausting day to find that my roommate’s new dog had gone up to my room and chewed:

1. The pump to my air mattress

2. A pair of gloves

3. Worst of all one just one of my black stilettos. I found a little gold buckle in the living room, and various pieces of black satin in a trail to the kitchen.

My first thought was that this dog needed to go to the pound–but my second thought was:

“Oh thank goodness he didn’t touch my XtraTufs!” *

This was the story that I told people back home in Haines, and more often than not it got a laugh; but the tale of the mangled stiletto also demonstrates how important it is to have the right footwear in Alaska. Fishermen in southeast put on a pair of Xtra tuffs, while workers in the interior have depended on bunny boots and even here on campus when the thermometer reads -20ºF students cannot walk around in anything less insulated than snow boots. Without coats and boots and hats and gloves the Alaska elements could be life threatening. Climate shapes daily life in Alaska, and regardless of maps or GPS, each Alaskan has an intimate relationship with the weather outside.

While most people associate Alaska with harsh weather, for several years after statehood Americans both in Alaska and the lower 48 had difficulty understanding how Alaska fit within the geographic context of the rest of the United States. After all, at the nearest point Alaska is 500 miles removed from the contiguous states and 1/5 the size of the rest of America.

After Alaska attained statehood in 1958, cartographers struggled with this new northern state, ultimately deciding to place Alaska in an inset south of California. A 1958 title in the New York Times read “Alaska as State no Map Problem,” with the subtitle “Cartographers Aim to Keep it an Inset Off West Coast, but with New Coloring.” The article continued, correctly supposing that Hawaii would join Alaska in a box the following year.

Maps of the United States included the detached 49th and 50th states until 1975 when Senator Ted Stevens spearheaded an effort to create the first USGS map displaying an accurately proportioned Alaska in the Arctic Circle and Hawaii in the Central Pacific. Following the release of the USGS map, the office of Senator Stevens sent copies to every school in Alaska. Teachers across the state responded with requests for duplicates so that students would understand Alaska’s location within the United States.

An accurately proportioned map can easily communicate the position and size of a state, and some geographic features like mountains, coastline and rivers. But another aspect of Alaska that often is overlooked is geographic diversity. Much to the chagrin of Texas, Alaska is known for being a huge state, but it is hard to explain how the climate in Fairbanks differs from that of Dutch Harbor.

Subsequently in this exhibit I wanted to communicate geographic diversity. I felt lucky to be able to work with Angie Schmidt at the Alaska film archives who put together a collection of film clips that show various maps of Alaska in addition to clips of Alaska scenery. In a campus full of students from various parts of the state I hope that those who walk through the gallery will be able to recognize something from home.

I also communicated regional differences through photography. Last summer and this fall I asked Alaska youth pre-K through high school to submit photos showing what their area looked like. In all we had about 50 photo entries from schools in southeast and south central Alaska; ten were selected for the display.

Geographic familiarity also extends to the university level, and Alaska is full of undiscovered research possibilities. Modern technology, GPS especially, has revolutionized how we chart remote areas. I talked to a couple of scientists at University of Alaska Fairbanks who sent spectacular photographs of their research. One came from Dr. Chris Larsen who monitors over 150 glaciers across Alaska and another came from Caitlin Smoot, a fellow graduate student who is working with Dr. Russell Hopcroft to investigate marine life in the Beaufort Sea.

Of course these are highly specialized uses of GPS, but the public uses GPS every day. One recreational activity is geocaching. Essentially, geocaching is a treasure hunt where individuals hide caches and then register the latitude and longitude online so that fellow seekers can find the cache. In short, geocaching is a quest with an updated compass and a digital treasure map.

Maps and weather and landmarks are a part of Alaska life. While familiar landmarks remain guiding features, maps and new technology are changing how we view our surroundings. Photographs and film can instantly remind someone of home while GPS readings can pinpoint glacial changes and geocaches. But whether you travel by plane, by boat or by car—in Alaska, it is always advisable to bring the right pair of shoes.

*XtraTufs are a brand of neoprene rubber boots originally created for commercial fishermen.

To see Susannah give the talk on youTube vider, go to our Stevens YouTube page: http://www.youtube.com/user/tedstevensproject/featured