Author Archives: otcgeorge

Ted Stevens Day 2012!

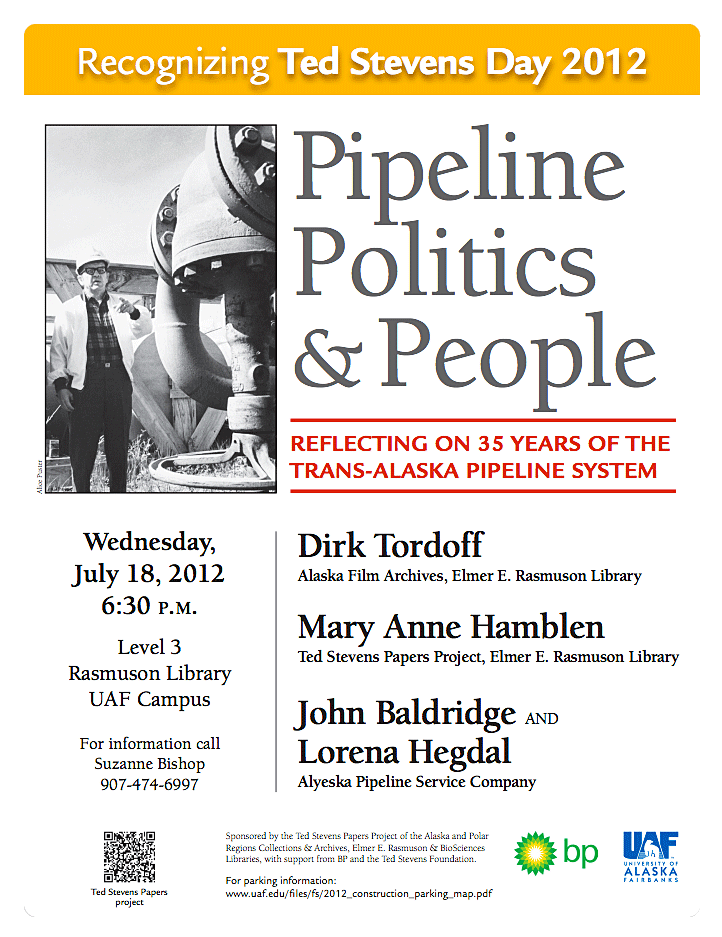

The Ted Stevens Papers Project celebrated Ted Stevens Day 2012 with a gallery talk and reception, Pipeline Politics & People: Reflecting on 35 Years of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, featuring speakers Dirk Tordoff, Alaska Film Archives; Mary Anne Hamblen, Ted Stevens Project Archivist; and John Baldridge and Lorena Hegdal of Alyeska Pipeline Service Company.

The accompanying exhibit, Pipeline Politics & People: Beginnings of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, highlights early legislation leading to the the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act (TAPS) signed by President Nixon in 1973, the “pipeliners” who came in droves in the mid-1970s seeking lucrative construction jobs, and the unique culture and camaraderie of the men and women who lived in the 29 temporary construction camps along the pipeline route.

The Technology & Transport portion of the exhibit features a model of an Alaska Air International Lockheed C-130 (“Hercules”) airplane, a tough military transport aircraft capable of using unprepared runways, used in the 1970s to support pipeline construction, and a mini-replica of a pipeline instruction gauge, or “pig,” used to clean and maintain the inside of operating pipeline.

The “Pipeliners” exhibit case, through photographs and artifacts, gives a glimpse into pipeline camp life and the people who worked on the pipeline. “Politics & Law” highlights critical legislation that paved the way for making TAPS possible, and the many politicians involved in crafting legislation and advocating for pipeline construction.

Read moreTed Stevens’ Uneasy Relations with Journalists and Journalism – One Reporter’s View

By Joel Southern, former Washington, DC correspondent for the Alaska Public Radio Network

”How can you stand to cover that guy?”

I can’t begin to count the number of times fellow reporters and others asked me some form of that question during the 19 years or so that I covered Sen. Ted Stevens. To call him irascible would be a gross understatement. There were times when he, by his own admission, could be a ”mean, miserable S.O.B.” – even to folks who were otherwise friendly to him. And he often channeled his comic book alter ego, The Incredible Hulk, when dealing with my ilk, particularly reporters for national news organizations that only paid attention to Stevens when he said or did something controversial or when he got mired in ethical or legal problems.

There were times when Stevens – quite frankly – was a royal pain in the rear-end to cover. But those of us who reported for Alaska news organizations also got to see a different side of him. We frequently sat down and talked with Stevens at length and in settings in which he was more at-ease than he was during the crazy, jam-packed Tuesday-Thursday work week typical of the U.S. Senate. Sure, even in those sessions, he could be cantankerous. But we also got to see him as a smart, wily, thoughtful and even funny person – he often used wry humor and even cracked jokes. It was also during those sessions that I came to marvel at what Stevens had done and who he had known or met during his long public life. For me, it was like being just one degree of separation from a fairly big slice of history that spanned more than 50 years.

In my view, reporters and Stevens had a complicated love-hate co-dependence. For us, he was a fantastic catalyst for news (particularly when he reached the pinnacle of his power in the Senate), even though it often was tough to deal with him and the methods he used to control information about what he was doing. As for Stevens, he craved good press and the recognition that could bring for the actions he took in behalf of Alaska and his other legislative interests. But, more often than not, he expected to get the shaft from reporters, so he was wary of dealing with us.

I think Stevens’ notion of how he ideally wanted Alaska news organizations to relate to him was formed back during the push for statehood, when he was Interior Secretary Fred Seaton’s pointman on the issue. Because of Stevens’ ties to Fairbanks, he was very close to News-Miner publisher Bill Snedden. And Stevens’ views of statehood and future resource development in Alaska resonated with those of long-time Anchorage Times chief Robert Atwood. In fact, Atwood’s daughter was an assistant to Stevens at the Interior Department, and one of the tactics Stevens used to push statehood was to have canned editorials written up and shopped out to newspapers nationwide. The two Alaska newsmen supported Stevens’ efforts to get other newspaper editorial pages and publishers on board. Sec. Seaton himself had come from the newspaper business, so his connections also helped get those editorials published.

On numerous occasions when Stevens thought he was getting too much flak from news organizations, I heard him refer back to the good old days when he thought of himself and the Alaska media as being on the same team. He felt particular animus against the Anchorage Daily News. During the years I covered Stevens, his litany of grievances against the ADN and some of its editors and reporters was long. He did not like the way the ADN covered and critiqued his efforts to open the Arctic Refuge coastal plain to oil development, to halt curbs on timber harvesting in the Tongass National Forest and to push a host of other contentious federal-state issues. The complaints only got louder and more bitter when the ADN raised questions about Stevens’ ethics and doggedly reported on the Bill Allen-VECO scandal, which ultimately knocked Stevens off his political throne. There seemed to be a personal element to Stevens’ raw feelings about the ADN because, as a private practice lawyer back in the 1960s, he had helped handle legal issues when Larry and Kay Fanning purchased the newspaper and developed a friendship with them. While Stevens did not always agree with the views published in the ADN, he had a more beneficent view of it when Fannings were in charge. But his attitude about the ADN soured after it was bought by the McClatchy newspaper chain in 1979.

Like most politicians, Stevens probably would have preferred for all of us in the news media just to reprint his press releases or pull sound bites from canned recorded statements he made. Of course, that is not what good, professional news organizations do and, at the end of the day, he understood that. I think what Stevens wanted most of all from reporters was a sense that we had done our homework, that we tried to understand why he pursued the goals he pursued, and that he felt we were treating him fairly. If he respected a reporter and felt he was being treated fairly, he was willing to engage in give-and-take.

I think one of Stevens’ favorite sparring partners in the press was David Whitney, a former McClatchy Newspapers reporter who was the ADN’s Washington correspondent when I started as APRN’s DC reporter. Whitney was an extremely smart and resourceful reporter who had a knack for rooting out stories about what Stevens was doing, often before the senator was ready for that information to be made public. On one occasion, Whitney was in a toilet stall when Stevens happened to walk into the same restroom, talking with another person about a hush-hush topic. Whitney quickly started taking notes and got himself a good news story. On another occasion, Whitney was pursuing a contentious story and needed a comment from Stevens. He finally caught up with the senator on the US Capitol steps, where Stevens was waiting to have his picture taken. Whitney called out to get Stevens attention, and Stevens flipped Whitney a middle finger in return – just as the photographer snapped the picture. According to aides, the photo remained in Stevens files a long time. When David, after many years, decided to move to another beat, Stevens had a little going-away ceremony in S-128, an ornate Senate Appropriations Committee hearing room in the Capitol. Stevens had hoped to give David a print of the photo as a gag gift. Aides could not find it, so instead David got a box containing a glove, which had all but the middle finger folded back.

Stevens also gained respect for me and my reporting, and that got me through some tricky situations with the senator – including a couple of times when he got angry with me for reporting exactly what he said, in his own recorded words.

Back in the mid-1990s, the congressional delegation got into a big fight with the U.S. Forest Service over timber harvesting levels in the Tongass Forest and long-term timber supply contracts for two southeast Alaska pulpmills. When Ketchikan began feeling the impact of the timber harvesting curbs, the delegation looked at ways to shift Forest Service administrative offices from Juneau to Ketchikan. After a hearing one day, I talked to Stevens and found out that he was also thinking about trying to move the Coast Guard’s Alaska regional headquarters to Ketchikan. I recorded the interview and then sent it to colleagues in Juneau. When Juneau officials heard what Stevens had said, they got angry, immediately called Stevens’ office in DC and raised a ruckus. Stevens backed off, and he laid low from me for a while. After several days, I saw him at a news conference on another issue, and he warily approached. He pointed at my microphone and said, ”That thing gets me into trouble.” I didn’t respond to that out loud, but thought, ”No, Senator Stevens. It was your mouth got you into trouble – not my microphone.” After that, things got back to normal, and we moved on.

There was another, more serious, time when Stevens froze out me and other Alaska reporters in D.C. – again, for reporting what he said. It came in October of 2003, at a time when Stevens was trying to bar Alaska tribes from directly receiving court, law enforcement and housing funds and also trying to find out if there were any very small “ghost villages” fraudulently receiving federal funds. Except for a couple of tribes, Stevens had been opposed to federal recognition of others in Alaska stretching back to his work on statehood in the 1950s, and he was outraged by the formal listing of more than 200 tribes by Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Ada Deer during the Clinton Administration.

During a sit-down with us one day, a colleague from another news organization asked Stevens about efforts by tribal sovereignty advocates to set up tribal courts in rural villages and whether tribal and state courts could co-exist. Stevens replied, ”It’s a very difficult thing. The road they’re on now is the road of destruction of statehood because the Native population is increasing at a much greater rate than the non-Native population. I don’t know if you realize that. And they want to have total jurisdiction over anything that happens in a village without regard to state law and without regard to federal law. Very serious, but people seem to laugh it off and say, ‘There goes Stevens again, he’s picking a fight with the Native people of Alaska.’ Not so at all. I’m trying to give them protection of the American system.”

But after he said that, I sat there and thought to myself something like, ”Does he really mean that, and does he understand how that’s going to sound to a lot of the Alaska Native community?” I did not for a moment believe that Stevens was racist toward Alaska Natives – over and over again during his time in public office, he had done many things to help them. But I also thought that what he said was newsworthy. So, I went back to my office, called colleagues in Anchorage and asked them to assess whether they did too. They did – and that set off a fight with Stevens that lasted for weeks.

After APRN aired Stevens’ comments, some tribal sovereignty advocates got angry and lashed out at Stevens. A Native woman who worked for an Alaska Native/rural village advocacy group and who had her own long record of service to Native causes told media outlets that the comments sounded racist, though she stopped short of calling Stevens himself a racist. Even so, Stevens got angry about it, and the woman’s employer, apparently out of fear of retaliation from Stevens, fired her in a matter of days. Stevens then cut off me and the rest of the D.C.-based press corps and set out to excoriate anyone and everyone he thought was accusing him of being racist. In a recorded speech to the annual convention of the Alaska Federation of Natives, he strongly defended his record of Native advocacy. He said the accusation of racism was a ”stain on his soul” and that being ”called ‘racist’ after more than 50 years of dedicated service to Alaskans, particularly Alaska Natives, is something I will not forget.” He repeated his concerns about footing the bill for tribal sovereignty in Alaska, saying ”It is just not possible to fund 231 separate villages as tribes.”

It seemed as though Stevens’ filibuster against the Alaska press corps in D.C. was never going to end. He was adamant, but I felt that I and APRN were justified in putting his comments on the air. Stevens often used strong, over-the-top rhetoric – he would just let it rip and not think about or care about the consequences. This was a case in which I believed that people deserved to hear what he had said and that he needed to be held accountable for his words. (The one thing I regret is that the Alaska Native woman who dared to comment about them was fired.) But then came a turning point. Stevens backed away from pushing his proposed curbs on tribal funding and instead lent his support to the concept of a federal/state/Native commission to assess rural Alaska justice and law enforcement issues. And, to his credit, he got over his anger and once again opened his door to me and the other D.C.-based reporters.

Reporting on Stevens became both difficult and interesting when he was under federal investigation for corruption allegations stemming from VECO chief and one-time friend, Bill Allen. Stevens was hounded daily by reporters from TV networks and newspapers nationwide. Phalanxes of reporters pursued a tight-lipped Stevens as he made his way down the hallways of the Capitol and the Senate office buildings. He frequently used restricted-access hallways and stairways to avoid reporters. When he did talk, he put on his old trial lawyer’s hat. He used the legal defense process and legalistic lingo to dodge questions about whether he had been called before a grand jury, was expecting indictments and – fundamentally – whether he had done anything wrong. He stuck very close to his “no comment” regime, but a time or two he got so fed up with the questioning that he said things that scared the wits out of his lawyers.

The situation put the D.C.-based Alaska press corps in a bind. The corruption investigation was just about the only thing that other reporters wanted him to talk about. We wanted to ask him about it too – but he was also deeply involved in a host of other issues of interest to our listeners, viewers and readers. If we asked too much about the corruption investigation, we ran the risk of torpedoing our chances of talking to him about those other things. At one point, Stevens became so anxious about it all that, at least for a while, he carried a small recorder around to record what reporters asked him. That happened to me one day. I caught him going from the Capitol to a Senate office building because I wanted to talk to him about something completely different than the corruption investigation. He agreed to talk, but stood there recording me as I recorded my interview with him.

There remains in my mind a question as to whether Ted Stevens might have pursued libel/slander/defamation claims against news organizations or individuals if he had been cleanly acquitted of the corruption charges by the jury at his federal court trial. During one session that I and McClatchy/ADN reporter Erika Bolstad had with him in November of 2007, he seemed to suggest he was pondering it. ”Your papers print those people who have been convicted and my son’s name and mine at the same time. You know, as far as the public is concerned, it’s all the same bale of wax. Now, I’m not going to comment on that bale of wax. But we’ve been included in a way that – I hope people understand the laws, that are doing it. Because, when it’s all over, some people are going to have to account for what they’ve said, and what they’ve charged us with,” he said. But he also refused to elaborate when we tried to get him to explain what he meant.

Audio Clip: Reporters Erika Bolstad and Joel Southern interview Senator

Despite the tough and frustrating times I had covering Sen. Stevens, it was a fascinating experience all in all. When I was just about ready to leave my job with APRN and Washington, D.C. in 2008, I sent a handwritten note to him. In essence, it said that, while not every day covering him had been a joy, it had been a great experience for me because I had learned much about the Congress, Alaska, the nation and the world.

And, for that, I will always be grateful to Ted Stevens.

Read moreOur Congress: A bill’s journey into law

A bill is a proposed law in Congress. Anyone with an idea for a bill may draft one, but it must be sponsored by a member of the House of Representatives or the Senate. Bills can be public, addressing groups of people, or private, concerning an individual, such as a grant of citizenship or an armed service decoration. Once a bill has a sponsor, it is placed in a box called a “hopper,” introduced by the majority floor leader of the House and assigned a number. (The majority floor leader is chosen by his or her party to represent that party in the Senate or House. The Senate Majority Leader for our 112th Congress is Harry Reid (D-NV) and Mitch McConnell (R-KY) is leader of the House. For more information on party leaders go to this page on the US Senate website.) After introduction, the proposed bill then goes to an appropriate committee for research and study. Informational hearings are held, and often the proposed legislation will be assigned to a subcommittee for further study. Next, the committee votes to report the bill, or to take no more action. If reported, a date is set on the calendar for a general debate on the floor of the House, with both parties receiving the same amount of debate time. The next step is the amending phase, where amendments to the bill are made, which can kill a bill or make it more palatable to the opposition. A lively debate can win notoriety and publicity for a representative. After amendments are made, the House votes, and if accepted the bill passes to the Senate, as bills must be approved by both chambers of Congress. The Senate is a smaller body than the House, with less formal rules, and time for debate is theoretically unlimited. This can lead to a filibuster, where a senator can speak for hours, as long as he or she can remain standing, in order to delay, defeat or amend a bill. When debate is finished, the Senate conducts a roll call vote to decide if the bill will pass or fail. If the “yeas” have it, the bill goes to the President to sign or veto. Hundreds of bills are introduced in each two-year Congressional session, although few make it out of committee for debate.

Read morePower of the black mark redaction

SUBMITTED BY MARYANNE

In mid-February, the FBI posted nearly 3,600 pages of information gathered about Senator Ted Stevens in over 50 years of Stevens’ service to the State of Alaska. Much of the material was already public source available elsewhere, such as news clippings. I’ve not spent a great deal of time with the files, but most engaging to me is the older material that provides glimpses into the political climate in the era surrounding Alaska’s early statehood. Aside from interesting items of a historical nature, Stevens’ released FBI files, complete with obligatory redactions, turned out to be a nonstory, but it did get me thinking about the thorny and very current issue of the FOIA, the United States’ Freedom of Information Act, and suspicion of government secrecy. Although the FBI often releases posthumously the files of well-known public figures, the release of Stevens’ files was the result of a FOIA request.

The Freedom of Information Act became a federal law in 1966, establishing the public’s right to information in the records of public agencies. Anyone may file a FOIA request to any federal agency entity or branch. The process can be lengthy, and there are several exemptions to FOIA by which a request can be denied, such as items containing national security information, the right to personal privacy, or confidential business information. In the early application of FOIA, resistance from government bureacrats often took the form of foot-dragging in supplying requested information, and before the practice of redaction became standard, access could be denied to material containing one restricted item in a document that otherwise would be made available. Changing political climates influence the secrecy/openness power struggle. A shift in public perception of government occurred in the 1930s, amid changes in the role of federal agencies under the Roosevelt administration. Agency bureacrats realized more power in crafting and administering public policy through Depression-era New Deal programs such as the Citizens Civilian Corps (CCC), the Securities and Exchange Commision (SEC), and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Fears of a too-powerful government grew among some in the constituency; a theme that continues today. The underpinnings of the 1966 FOIA began in the 1930s with journalism professor Harold Cross, a severe critic of what he believed was an overreach of power by President Roosevelt. The Cold War chilled progress toward a more transparent government under the Truman and Eisenhower administrations. In 1950, as legal counsel to the American Society of Newspaper Editors, Cross proposed a new law addressing the people’s “right to know “ and access to government records that became the basis for the first iteration of FOIA. The Watergate scandal, leading to President Nixon’s impeachment, impacted the public’s perception of transparency standards in government, and in 1974, Congress passed amendments to the original FOIA bill, loosening restrictions. Exploring the culture of government secrecy versus public perception, cultural anthropologist Michael Powell posted an essay in the Huffington Post in December 2010, Shadow Elite: WikiLeaks, FOIA and the Cultural Life of Government Secrecy. Powell observes that the custom of redaction on FOIA requests began as one of the 1974 FOIA amendments, with the purpose of allowing release of more records while also protecting privacy. Powell points out the irony that black-marker redactions soon became an icon for cover-up, a symbol for unchecked government power in the public imagination. Redaction functions as a red flag, empowering people, stimulating questions and raising awareness about legitimate uses of power and possible misuse. Julian Assange, editor in chief of WikiLeaks, dramatically entered the transparency/secrecy power play recently with his outing of classified diplomatic documents, ostensibly in the spirit of total governmental openness. lt can be argued that the threat of total transparency may keep sensitive records from being created at all. Whether or not WikiLeaks’ document dumps will usher in a new transparency in government and a new power redistribution, or create a reinvigorated climate of secrecy remains to be seen.

The struggle to find a balance between transparency and secrecy should not stop. I agree with Powell: “Black marker redaction doesn’t stop communication. It is an invitation for suspicion, skepticism and paranoid interpretation. The word may be gone, but a form and trace remains. We become aware that we cannot know something that we want to know–and that gets us wanting to know why we can’t know. And this is actually a very healthy kind of paranoia for a democratic society to have.”

Read moreTed Stevens, lifelong sports advocate

SUBMITTED BY MARYANNE

As the Ted Stevens Papers Project progresses, materials processed so far make it clear that Senator Stevens had a vested interest in sports on and off the Hill. An avid tennis player, he was able to see the value in sports and recreation reflected in both his personal and professional lives. This is evident through numerous photographs of Stevens with professional athletes who looked to Stevens as a role model and protector of their rights to sports, and also through photos of the Senator himself participating in health and wellness activities. Additionally, Stevens’ crafting of, and impact on, legislation regarding equal access to athletic opportunities is apparent . Constituents and peers respected Senator Stevens’ staunch support of sports through any avenue available.

Stevens reputation for standing behind sports, and equality in sports, is reflected in two primary pieces of legislation that embody his belief that equal access to sports is an individual right, and a responsibility of the government to protect. Title IX, supported by Stevens as part of the Equal Education Amendments Act of 1972, and the Amateur Sports Act of 1978 came to define his political stance regarding sports. Title IX provided that young women would have an equal opportunity to their male counterparts to participate in school athletics and other sports programs, and his support gained him the reputation of ‘protector’ of Title IX. As a sponsor of the Amateur Sports Act of 1978, Stevens was a leader in crafting the legislation, working to establish the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), and National Governing Bodies (NGBs) for each individual sport, as well as providing legal protection for individual athletes. The 1978 Act was revised in 1998 to reflect the reality that many competitive athletes were not “amateurs”, expand the USOC’s domain to include the Paralympics, and establish avenues to provide athletes with advice and advocacy on grievance procedures. Rosey Fletcher, a lifelong Alaskan and three time Olympian who benefited from the passage of the Acts, claimed in the Anchorage Daily News in November 2011 that Ted Stevens’ name warrants a place in the Sports Hall of Fame for his contributions to athletes of all ages and abilities.

Similarly, both the USOC and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) observed the impact Stevens’ support had on athletes and sports. The IOC recognized Stevens by presenting him with their highest honor of the Olympic Order; Stevens became the first member in Congress to receive the award from the IOC. The USOC awarded Stevens the Olympic Torch Award, the highest honor presented to individuals in recognition of outstanding service in the US Olympic movement. Most recently, in 2012 Stevens was inducted posthumously into the US Olympics Hall of Fame for his contributions to the Olympic movement.

Read more